Alternative Solmization Methods in Germany and Belgium

This post explores some of the alternative methods of solmization that emerged from the Guidonian hexachordal system in Germany and Belgium from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. While none of these systems is currently widely used, each had strong contemporary proponents on a local scale, and each provided a different solution to the issues faced by singers in dealing with hexachordal mutation by adding a seventh and/or eighth scale degree to the solmization format.

Issues with the Hexachord

The Guidonian system of solmization was based on the hexachordal syllables ut, re, mi, fa, so, and la, in which the starting pitch of ut could be shifted to various pitches so as to accommodate the entire gamut. The natural hexachord was built on C as ut; the hard hexachord, on G as ut; and the soft hexachord, on F as ut. These latter two were so named due to the quality of the B encompassed in the hexachord-- either the "hard" or "square" (natural) b-quadro or the "soft" (flat) b-molle. In order to sing pieces on solfege with a range outside a single hexachord, performers would engage in mutation, the substitution of a pitch from one hexachord for that of another. For example, to sing a continuous stepwise ascent starting on G in cantus durus, one could begin with the ascending hard hexachord with G as ut, A as re, B as mi, and C as fa, then mutate on D from sol to re in order to continue in the natural hexachord, where C is ut, D is re, E is mi, F is fa, and so on. Points of mutation were dependent on mode, along with whether a singer was ascending or descending in the scale: a descending scale in cantus durus would mutate not at sol/re (D) but at mi/la (E) as a common point between the hard and natural hexachords.

The criticisms of hexachordal mutation were twofold: for music requiring a wide range, the number and frequency of mutations quickly became impractical (particularly for the more chromatic music emergent in the eighteenth century), and for those just learning to sing, it was deemed by a number of theorists and scholars to be overly complicated from a pedagogical standpoint. According to a 1600 account by German theorist Sethus Calvisius, the practice of mutation was well-known to create "difficulty for beginners." Johannes Lippius, writing in 1612, went even further: mutation was "real torture for those learning to sing... [Singers] are absolutely right in continuing to press hard for [its] abolition, together with the mollis scale." Eighteen years later, the Calvinist academic Johann Henrich Alsted echoed this rhetoric, calling hexachordal mutation the "torture of tender wits" and the "torture of the Ingenious."²

The addition of the seventh scale degree si to fill out the diatonic octave gradually became a standard method of dealing with these issues. Its main advantage was that it associated each syllable with a distinct pitch class for a piece. However, the use of the ut-si heptachord was by no means immediate or universal, and the same principle of expanding the six-syllable system existed in several other more localized forms, such as bocedization, bebization, damenization, and the umbrella term "bobisation," all of which will be discussed below.

Bocedization (Voces belgicae)

"Bocedization" is the name given to a type of solmization commonly attributed to the Belgian composer, vocalist, and publisher Hubert Waelrant. It is also sometimes referred to as the voces belgicae system.

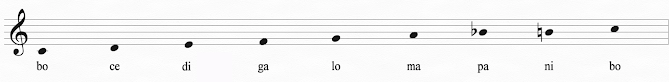

The bocedization syllables are typically seven in number, with an eighth sometimes added to represent the flat seventh scale degree¹:

One possible basis for the bocedization syllables is put forth by Renaissance music scholar Jessie Ann Owens, who notes the similarities between the consonants used for bocedization and those used for Byzantine solmization. Owens observes that Byzantine solmization, which followed the first seven letters of the Greek alphabet (αβγδεζη), resulted in the syllables pa, bo, ga, di, ke, zo, ni (with pa standing for α and ke representing ε).² This system could have been modified to fit what would be alphabetical order for the German language, with the main alteration necessary being the addition of ma as the sixth scale degree to form bo, ce (from ke), di, ga, lo (from zo), ma, (pa), ni.

Hubert Waelrant, often credited as the devisor of bocedization, is thought to have taught of singing at a music school he founded in Antwerp, ca. 1553-1556, although some later scholarship contests his role as the inventor of this system or the founder of the school. Musicologist Howard Slenk notes that the majority of extant information on Waelrant's pedagogical experience that links him to bocedization practices comes from a single source-- the writing of his pupil Sweertius-- and housing documents for the school in question do not name him as an official founder or as a solfege instructor specifically but as an unpaid tutor in singing for fellow musician and pedagogue Gregorius de Coninck, leading some scholars to doubt the extent of his involvement in its spread.⁴

However, while Waelrant is not cited in other primary sources as a founder of bocedization, there are several extant references to some form of bocedization existing in and around Belgium among contemporaneous theorists. Calvisius writes that "they have recently devised new musical syllables in the Low Countries... bo, ce, di, ga, lo, ma, ni, bo"; similarly, Lippius refers to bocedization as the "very concise and apt notation invented in the Low Countries."² Thus, it is evident that this form of solmization was popularly associated with Belgian musicianship if not always Waelrant in particular.

Bebization and Damenization

There are records of at least two other German solmization methods, bebization and damenization, being used between the mid-1600s and mid-1700s. "Bebization" was the name given to German theorist Daniel Hitzler's solmization, which he describes in 1628 as follows:

These were fixed syllables corresponding to specific pitches, with "la" for A, "be" for B, and so on.³ Notably, the consonant for each corresponds to its place in the (German) alphabet with the exception of "la" and "me" for A and E, and all but "la" share the same vowel.

Damenization, meanwhile, was developed sometime around 1750 by the German vocalist and opera composer Carl Heinrich Graun.³ Unlike bebization, damenization featured differing vowel sounds for successive pitches:

Like bocedization, each of these methods appears to be regionally specific in nature, although neither is referenced as extensively in secondary theoretical and pedagogical texts.

"Bobisation" and Retrospective Assessment

In his Dictionary of Music, Hugo Riemann defines "bobisation" as "a comprehensive term for the different solmisation-syllable names given to the seventh note of the fundamental scale."³ In this category Riemann includes Hitzler's bebization, Graun's damenization, and the bocedization attributed to Waelrant, along with other miscellaneous syllabic distinctions between B flat and B natural (such as the use of bo for B flat and si for B natural, the use of bo and bi as in the name given to the broader phenomenon, and the use of bo and ba). While Riemann notes these were largely proposals with only "local influence," the numerous different syllabification methods point to a common interest in expanding the hexachord to minimize the necessity for mutation and in distinguishing between the flat and natural seventh scale degrees in a fixed-ut context.³ Their grouping under the label "bobisation" in Riemann's 1890 publication fixes these diverse methods retrospectively as a broad precursor to the use of si as the (single, natural) seventh scale degree.

~

Works Cited

1. Barnett, Gregory. "Tonal Organization in Seventeenth-Century Music Theory." In Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, edited by Thomas Christensen. Cambridge University Press, 2002: 407-455.

2. Owens, Jessie Ann. "Waelrant and Bocedization: Reflections on Solmization Reform." In Music Fragments and Manuscripts in the Low Countries; Alta Capella; Music Printing in Antwerp and Europe in the 16th Century, edited by Eugeen Schreurs and Henri Vanhulst. Yearbook of the Alamire Foundation 2 (1997), 377-393.

3. Riemann, Hugo, trans. J.S. Shedlock. Dictionary of Music. Augener & Co., London: 1896.

4. Slenk, Howard. "The Music School of Hubert Waelrant." Journal of the American Musicological Society 21, no. 2 (Summer 1968), 157-167.

Comments

Post a Comment